Bars in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia let out at 2

A.M. On the morning of January 17, 2010, two groups emerged,

looking for taxis. At the corner of Market and Third Street,

they started yelling at each other. On one side was Edward

DiDonato, who had recently begun work at an insurance company,

having graduated from Villanova University, where he was a

captain of the lacrosse team. On the other was Gerald Ung, a

third-year law student at Temple, who wrote poetry in his spare

time and had worked as a technology consultant for Freddie Mac.

Both men had grown up in prosperous suburbs: DiDonato in Blue

Bell, Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia; Ung in Reston,

Virginia, near Washington, D.C. Bars in the Old City neighborhood of Philadelphia let out at 2

A.M. On the morning of January 17, 2010, two groups emerged,

looking for taxis. At the corner of Market and Third Street,

they started yelling at each other. On one side was Edward

DiDonato, who had recently begun work at an insurance company,

having graduated from Villanova University, where he was a

captain of the lacrosse team. On the other was Gerald Ung, a

third-year law student at Temple, who wrote poetry in his spare

time and had worked as a technology consultant for Freddie Mac.

Both men had grown up in prosperous suburbs: DiDonato in Blue

Bell, Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia; Ung in Reston,

Virginia, near Washington, D.C.

Everyone had been drinking, and neither side could subsequently

remember how the disagreement started; one of DiDonato’s friends

may have kicked in the direction of one of Ung’s friends, and

Ung may have mocked someone’s hair. “To this day, I have no idea

why this happened,” Joy Keh, a photographer who was one of Ung’s

friends at the scene, said later.

Last year, mass shootings accounted for just two per cent of

American gun deaths. Most gun violence is impulsive and up

close. Last year, mass shootings accounted for just two per cent of

American gun deaths. Most gun violence is impulsive and up

close.

The argument moved down the block, and one of DiDonato’s

friends, a bartender named Thomas V. Kelly IV, lunged at the

other group. He was pushed away before he could throw a punch.

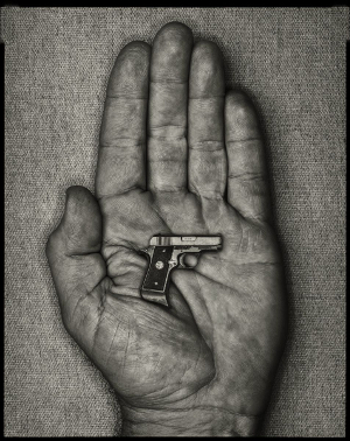

He rushed at the group again; this time, Ung pulled from his

pocket a .380-calibre semiautomatic pistol, the Kel-Tec P-3AT.

Only five inches long and weighing barely half a pound, it was a

“carry gun,” a small, lethal pistol designed for “concealed

carry,” the growing practice of toting a hidden gun in daily

life. Two decades ago, leaving the house with a concealed weapon

was strictly controlled or illegal in twenty-two states, and

fewer than five million Americans had a permit to do so. Since

then, it has become legal in every state, and the number of

concealed-carry permit holders has climbed to an estimated 12.8

million.

Ung had obtained a concealed-carry license because he was afraid

of street crime. He bought a classic .45-calibre pistol but

later switched to the Kel-Tec, which was easier to carry; for a

year and a half, he stowed one of the pistols in his pocket or

in his backpack. He had never fired it. Now, on the sidewalk, he

held the Kel-Tec with outstretched arms. A pedestrian heard him

yell, “You’d better not piss me off!” Ung maintains that he

said, “Back the fuck up.” DiDonato thought the pistol looked too

small to be real; he guessed that it was a BB gun. He spread his

arms, stepped forward, and said, “Who are you going to shoot,

man?” Ung pulled the trigger. Afterward, he couldn’t recall how

many times—he said it felt like a movie, and he was “seeing

sparks and hearing pops.”

Ung hit DiDonato six times: in the liver, the lung, the

shoulder, the hand, the intestine, and the spine. When DiDonato

collapsed, Ung called 911 and said that he had shot a man. On

the call, he was recorded pleading, “Why did you make me do it?”

DiDonato, in a weak voice, can be heard saying, “Please don’t

let me die.” When police arrived, Ung’s first words were “I have

a permit.”

More American civilians have died by gunfire in the past decade

than all the Americans who were killed in combat in the Second

World War. When an off-duty security guard named Omar Mateen,

armed with a Sig Sauer semiautomatic rifle and a Glock 17

pistol, killed forty-nine people at a gay club in Orlando, on

June 12th, it was historic in some respects and commonplace in

others—the largest mass shooting in American history and, by one

count, the hundred-and-thirtieth mass shooting so far this year.

High-profile massacres can summon our attention, and galvanize

demands for change, but in 2015 fatalities from mass shootings

amounted to just two per cent of all gun deaths. Most of the

time, when Americans shoot one another, it is impulsive, up

close, and apolitical.

None of that has hurt the gun business. In recent years, in

response to three kinds of events—mass shootings, terrorist

attacks, and talk of additional gun control—gun sales have

broken records. “You know that every time a bomb goes off

somewhere, every time there’s a shooting somewhere, sales spike

like crazy,” Paul Jannuzzo, a former chief of American

operations for Glock, the Austrian gun company, told me.

Sometimes the three sources of growth converge. On November 13th

of last year, terrorists in Paris killed a hundred and thirty

people and wounded hundreds more. On December 2nd, a husband and

wife, inspired by ISIS, killed fourteen people in San

Bernardino, California. This year, on January 5th, President

Obama announced executive actions intended to expand the use of

background checks. By the end of that day, the share price of

Smith & Wesson, the largest U.S. gunmaker, had risen to $25.86,

its highest level ever. After the attack in Orlando, shares of

Smith & Wesson rose 9.8 per cent before the market opened the

next day. Last week, the company reported that, in its latest

fiscal year, revenue grew thirty-one per cent, to a record $733

million. In a call with investors and analysts, Smith & Wesson’s

C.E.O., James Debney, said that he was “very pleased with the

results that we got.” He attributed the growth in firearm sales

to “increased orders for our handgun designed for personal

protection.”

The story of how millions of Americans discovered the urge to

carry weapons—to join, in effect, a self-appointed, well-armed,

lightly trained militia—begins not in the Old West but in the

nineteen-seventies. For most of American history, gun owners

generally frowned on the idea. In 1934, the president of the

National Rifle Association, Karl Frederick, testified to

Congress, “I do not believe in the promiscuous toting of guns. I

think it should be sharply restricted and only under licenses.”

In 1967, after a public protest by armed Black Panthers in

Sacramento, Governor Ronald Reagan told reporters that he saw

“no reason why on the street today a citizen should be carrying

loaded weapons.”

But the politics of guns and fear were changing. In 1972, Jeff

Cooper, a firearms instructor and former marine, published

“Principles of Personal Defense,” which became a classic among

gun-rights activists and captured a generation’s anxieties.

“Before World War II, one could stroll in the parks and streets

of the city after dark with hardly any risk,” he wrote. But in

“today’s world of permissive atrocity” it was time to reëxamine

one’s interactions with fellow-citizens. He ticked off the names

of high-profile killers, including Charles Manson, and wrote of

their victims, “Their appalling ineptitude and timidity

virtually assisted in their own murders.” Adapting a concept

from the Marines, he urged civilian gun owners to assume a state

of alertness that he called Condition Yellow. He wrote, “The one

who fights back retains his dignity and his self-respect.”

Soon armed citizens acquired a political voice: in 1977, at the

N.R.A.’s annual meeting, conservative activists led by Harlon

Carter, a former chief of the U.S. Border Patrol, wrested

control from leaders who had been focussed on rifle-training and

recreation rather than on politics, and created the modern

gun-rights movement. In 1987, the refashioned N.R.A.

successfully lobbied lawmakers in Florida to relax the rules

that required concealed-carry applicants to demonstrate “good

cause” for a permit, such as a job transporting large quantities

of cash.

Under the new “right to carry” laws, which two dozen other

states later adopted, officials had no choice but to issue a

permit to anyone who was “mentally fit” and had not been

convicted of a violent felony. Then the N.R.A. set about

extending the right to carry into places that had remained off

limits, including bars, colleges, and churches. Beginning this

fall, Texas will be the eighth state to allow students and staff

at public universities to carry on campus. (A smaller movement

advocates “open carry”—bearing unconcealed weapons in public—but

many gun owners consider that option counterproductive, because

it repels moderate allies.)

For gun manufacturers, the concealed-carry movement was a

lucrative turn. In 1996, the N.R.A.’s chief lobbyist, Tanya

Metaksa, said, “The gun industry should send me a basket of

fruit.” Small-calibre guns, like Gerald Ung’s .380-calibre, had

been regarded as a joke. “They were called ‘mouse calibres,’ ”

Jannuzzo said. “People were very disparaging.” But, as states

loosened their laws, gunmakers marketed those weapons as “true

pocket guns,” with “maximum concealability.” Ammunition

companies reëngineered small rounds to increase their velocity

and lethality. In 2014, manufacturers produced nearly nine

hundred thousand .380-calibre guns, more than in any previous

year, and a twenty-fold increase since 2001. In 1999, twenty-six

per cent of gun owners cited personal protection as their top

reason for buying a gun; by 2013, self-defense was cited more

than any other reason. “I see grown men grab a .380-calibre gun

out of the truck and put it in their pockets,” Jannuzzo said.

“It’s a whole new world out there.”

The Orlando massacre renewed calls to restore a federal

assault-weapons ban, which expired in 2004, given that

military-style rifles were used by killers in Orlando, San

Bernardino, at the Sandy Hook Elementary school, and in Aurora,

Colorado, among other places. But in 2014 rifles accounted for

just three per cent of the more than eight thousand gun

homicides recorded by the F.B.I. A ban would have a limited

effect on gun-industry profits. The right-to-carry movement, by

unbridling the presence of firearms in American life and

erecting a political blockade against efforts to qualify it, has

transformed the culture and business of guns.

The greatest legal and political questions around guns today are

not what types of weapons people will be allowed to use in the

future but who can use them and why. On June 9th, a federal

appeals court in California sided with gun-control advocates,

ruling that local governments can set conditions on the right to

carry concealed weapons. “This is the beginning of a battle, not

the end,” Adam Winkler, a specialist in gun law at the

University of California, Los Angeles, said. The Supreme Court

has ruled that Americans have a right to “self-defense within

the home,” but it has said nothing regarding what Americans can

carry in public “It’s the next great frontier for the Second

Amendment,” Winkler said.

Those who have taken to carrying concealed weapons often

describe the experience as a change that reaches beyond physical

self-defense. Laurie Lee Dovey, a gun-industry writer, reminded

me of the moment, in 2008, when Barack Obama was recorded saying

that small-town voters “cling to guns or religion.” Eight years

later, she said, those voters have upended American politics

with a populist surge in both political parties, and Obama’s

words no longer feel like an insult. “Of course I cling to my

guns and my religion!” Dovey said. “What’s wrong with that? It’s

the greatest phrase ever.” The expression has inspired pro-gun

T-shirts that say “Proud Bitter Clinger.”

Gerald Ung received his concealed-carry permit in Virginia. To

meet the requirements, he attended an N.R.A.

basic-pistol-shooting class. I was curious to know what that

involved, and on a recent Saturday morning I drove half an hour

from my home, in Washington, D.C., to the N.R.A.’s headquarters,

an office park of mirrored-glass buildings, in Fairfax,

Virginia. I’d been advised to take the Utah Multi-State

Concealed Firearm Permit Course. Utah’s permit is popular

because it is valid in at least thirty states.

Our class, which consisted of five men and a woman, met in a

room adorned with hunting trophies and a flat-screen TV. Our

firearms instructor, Mark Briley, Jr., announced that we would

not be touching any guns. “At the end of this class, you will

have weapons familiarity as defined by Utah,” he said. “They do

not require live fire.” (The N.R.A.’s lobbying arm opposes

minimum training and proficiency standards for carry permits,

calling them “needless mandates,” and it has successfully

spurred some states to eliminate them.)

Briley—father of three, African-American, goatee—wore black

cargo pants and a black polo shirt, and he had the qualities of

a great teacher: enthusiasm, patience, a sense of humor. “I was

going to a predominantly white church in Farmville”—population:

8,169—“and people said, ‘If you keep going with those white

folks, the next thing you know they’ll have you shooting guns

and riding Harleys.’ ” He now teaches shooting and rides a

Harley, he said.

Briley moved briskly through the lesson: we compared ammunition

malfunctions (a hang fire versus a squib load), defensive rounds

(the hollow point versus the full-metal jacket), and styles of

shooting (the Weaver stance versus the isosceles). Periodically,

he paused. “Any questions on any components of the semiautomatic

pistol frame?” There were none.

We reviewed different kinds of threats—home invaders, muggers,

druggies—and Briley urged us to “get out of the realm of just

thinking about people hurting us with weapons.” He said,

“Honestly, if they have arms, they’re armed.” He lingered most

on the risk of mass shootings. “We’re approaching a time here in

America where knowing the difference between concealment and

cover may be the difference between living and dying,” he said.

“What’s concealment and cover at a mall? What’s concealment and

cover at a movie theatre? There is no safe place.” He urged us

to scan every room with an eye for potential hiding places.

“Does it have plants? Are they fake or real? If they’re real,

does it have potting soil?”—which could deflect incoming fire.

“I’m always thinking.”

He warned us against trying to be heroes or losing our tempers.

We’d all heard of an argument over texting that erupted in a

Florida movie theatre in 2014. A man threw popcorn at a

fellow-moviegoer, who pulled out a .380-calibre pistol and

killed him. (The shooter, Curtis Reeves, Jr., who has pleaded

not guilty, is awaiting trial for second-degree murder.) Briley

warned us against ending up in court in what he called “today’s

anti-gun climate.” He quoted his grandmother: “ ‘Marky, there’s

a reason they call it the criminal justice system.’ I said,

‘Why?’ She says, ‘Because the criminals get the justice and

you’ll get the shaft.’ ”

We moved on to the law, and Briley, cautioning that he was not

giving legal advice, pulled up the text of Utah Code 76-2-402,

and read it aloud with the speed of an auctioneer: “A person

does not have a duty to retreat from the force or threatened

force . . . in a place where that person has lawfully entered or

remained.” He put it plainly: “So Utah would be what we call a

Stand Your Ground state. Let me tell you this: Stand Your Ground

is not a blank check to use your firearm. It just says, ‘I don’t

have to retreat.’ ” He brought up George Zimmerman, the

neighborhood-watch volunteer in Florida, who, in 2012, claimed

self-defense in fatally shooting Trayvon Martin, an unarmed

black seventeen-year-old. Nearly three years after Zimmerman was

acquitted, he has critics as well as admirers in the gun

community. In May, he tried to sell at auction the gun that he

used to kill Martin. The auction was sabotaged—at one point, a

leading bidder registered as “Racist McShootface”—but he

auctioned it again a few days later and reportedly received two

hundred and fifty thousand dollars.

Briley urged us to see Zimmerman’s story as a warning. He said,

“Who would trade places with Zimmerman today? No hands ever go

up in any class I’ve asked that question.” Briley went on, “The

growing concern I have about folks in the concealed-carry

community is that we don’t look at less than lethal options as a

part of our tool kit.”

We finished class on schedule. We had been there four hours, and

I had fulfilled all training requirements to receive my

concealed-carry permit. I was home in time for lunch.

Americans have come to accumulate three hundred and ten million

firearms, and to understand how they achieved this it’s useful

to visit the home town of the gun business. Most gun owners

today are in the South and the West, but most gunmakers are in

New England, because in 1794 George Washington picked

Springfield, Massachusetts, to make military weapons. The

Springfield Armory, which trained early gunsmiths, such as

Horace Smith, spurred the construction of factories along the

Connecticut River. It’s still known as Gun Valley.

As a business proposition, guns suffer from an irreparable flaw:

they last a very long time. Therefore, the industry constantly

needs new customers or novel ways to sell more guns to old

customers. (It was Samuel Colt who is said to have coined the

phrase “new and improved.”) These days, the business relies

mostly on old customers. In 1977, more than half of all American

households had a gun in the house. By 2014, it was less than a

third. Each gun owner now has an average of eight guns,

according to an industry trade association.

Mike Weisser entered the gun business in 1965 and has worked as

a wholesaler, a retailer, an importer, and an N.R.A.-certified

instructor. At seventy-one, he is a blunt and voluble

storyteller who lives outside Springfield, with his wife,

Carolyn, a pediatrician. Weisser received a doctorate in

economic history from Northwestern, and has taught at the

University of South Carolina and elsewhere. “The first home

movie of me was at the age of five, twirling a plastic

revolver,” he recalled. In 2001, he bought a storefront in Ware,

Massachusetts, and over the next thirteen years he sold, by his

estimate, twelve thousand guns, while writing six books. As a

blogger, he is known as Mike the Gun Guy. On a recent morning in

Springfield, Weisser pulled his car up to a vast brick factory

complex that once held the headquarters of Smith & Wesson. In

the seventies, Weisser was a Smith & Wesson distributor, and

business was steady. “They had a lock on the police market,” he

said. “They had a certain number of guns they made every year.

It was very quiet.”

But by the late eighties American gun manufacturers were facing

two serious problems: popular European imports, such as Glock,

were luring away police and military consumers; and hunting,

once a reliable market, was in decline as rural America emptied

out. In 1977, a third of all adults lived in a house with at

least one hunter, according to the General Social Survey; by

2014, that statistic had been halved. Weisser said, “The gun

industry, which had been able to ride on an American cultural

motif of the West, and of hunting, is realizing that’s gone.

Plus, you’ve got the European guns coming in that are so good

that the U.S. Army is even using them. Jesus Christ Almighty,

we’re fucked.” In 1998, an advertisement in Shooting Sports

Retailer warned, “It’s not ‘who your customers will be in five

years.’ It’s ‘will there be any customers left.’ ” Richard

Feldman, a high-ranking N.R.A. lobbyist in the eighties, who

worked as a liaison to the industry, told me that companies

looked for ways to make up for the decline of hunting: “You’re

selling whatever the market wants. It doesn’t matter where you

make your money. It’s irrelevant.”

A solution, of sorts, arrived in 1992, when a Los Angeles jury

acquitted four police officers of using excessive force in the

beating of Rodney King. The city erupted in riots. “It was the

first time that you could see a live riot on video while it was

going on,” Weisser said. “They had a helicopter floating around

when a white guy pulled up to the intersection. These black guys

pull him out of the truck and are beating the shit out of him

right below that helicopter.” The new market for self-defense

guns was born, Weisser said, and it was infused with racial

anxiety. “That was the moment, and if you talked about ‘crime’

everybody knew what you meant.”

Selling to buyers who were concerned about self-defense was even

better than selling to hunters, because self-defense has no

seasons. The only problem, from a marketing perspective, was

that America was becoming, by any measure, a less dangerous

place. Violent crime peaked in 1991, during the crack-cocaine

era, and has dropped by almost half since then. Victimization

rates of rape or sexual assault are down sixty per cent from

their historic highs. (The reasons for the decline are debated,

but most scholars credit a combination of an improved economy,

more police, better technology, and a broad decline in alcohol

use.) Nevertheless, in a 1997 article in the magazine Shooting

Industry, Massad Ayoob, a popular pro-gun writer and trainer,

urged dealers to seize the opportunities created by the new

concealed-carry laws: “Defensive firearms, sold with

knowledgeable advice and the right accessories, offer the best

chance of commercial survival for today’s retail firearms

dealer.”

By the end of the nineties, the gun industry was ailing again.

Inspired by lawsuits against the tobacco industry, more than

thirty local and state governments had sued gun manufacturers.

The N.R.A. refused to settle, but the suits were damaging. In

one case, a whistle-blower named Robert Hass, who had been Smith

& Wesson’s marketing-and-sales chief, said that companies knew

far more than they admitted about how criminals obtained guns,

and that “none of them, to my knowledge, take additional steps .

. . to insure that their products are distributed properly.”

This time, a gunmaker thought he had a solution—one that would

not only sell more guns but lower the toll of gun violence. Ed

Shultz, who was then the C.E.O. of Smith & Wesson, had grown up

attending a one-room schoolhouse, the son of an Iowa hog farmer.

Though he called himself a “rabid gun owner,” he was also a

pragmatist: easygoing with the press, and experienced. He had

manufactured lawnmowers, furniture, bicycles, and other goods.

In the hope of ending the lawsuits, he secretly agreed to

negotiate with the Clinton Administration. To avoid detection,

the talks were held in airport hotels and obscure federal

offices. After six weeks, the negotiators were near a deal, and

Shultz was sitting across from the Administration’s point man,

Andrew Cuomo, who was Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Housing and

Urban Development.

Cuomo, now the governor of New York, told me recently, “I was a

gun owner at the time, and I have kids in the house.” He said to

Shultz, “If you tell me you could sell a gun that my child

couldn’t operate, even if it was sitting on the counter, loaded,

that is appealing to me.” In the late nineteenth century and the

early twentieth, Smith & Wesson manufactured more than half a

million handguns with a two-part safety that the company boasted

was “perfectly harmless in the hands of a child,” but it

abandoned them during the Second World War, when it focussed on

producing military guns. Shultz was open to building a new,

high-tech version—a “smart gun” that could be fired only by its

owner. “He says, ‘I’m not interested in any political statement.

I’m interested in a business-survival strategy,’ ” Cuomo

recalled.

On March 17, 2000, Clinton and Cuomo announced the deal: among

other things, Smith & Wesson agreed to develop a smart gun and

take steps to prevent dealers from selling to criminals. Cuomo

declared, “We are finally on the road to a safer, more peaceful

America.” But on the day the deal went public the N.R.A.

denounced Smith & Wesson as “the first gun maker to run up the

white flag of surrender.” It released Shultz’s phone number, and

encouraged members to complain. He received many threats. One

caller said, “I’m a dead-on shot, Mr. Shultz.” Another executive

took to wearing a bulletproof vest, according to “Outgunned,” a

history of gun-control politics, by Peter Harry Brown and Daniel

G. Abel. Online, a boycott took hold, and sales of Smith &

Wesson guns fell so sharply that two factories temporarily shut

down. In ten months, the stock lost ninety-five per cent of its

value, and the company was sold the next year for a fraction of

its former worth.

Shultz left the company, and he all but stopped talking to the

press. When I happened on a phone number for him, he called me

back only to ask how I’d found it. “I need to know where the

hole is, so I can plug it,” he said, and declined to talk about

the gun business.

With the help of Congress, the industry has avoided further

lawsuits. In 2005, the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act

immunized gun manufacturers, distributors, and dealers from

civil liability for damages caused by their products. Mike

Fifer, the C.E.O. of the U.S. gunmaker Sturm, Ruger, said at an

N.R.A. convention in 2011 that the law is “probably the only

reason we have a U.S. firearms industry anymore.”

Smith & Wesson has repaired its relationship with the N.R.A. In

2012, Debney, the current C.E.O., was inducted into the N.R.A.’s

Ring of Freedom, the highest rank of donors, reserved for those

who give at least a million dollars. He received a yellow sports

coat and was featured on the cover of an N.R.A. magazine,

wearing the jacket and holding a concealed-carry gun. Smith &

Wesson underwrites several N.R.A. initiatives, including “The

Armed Citizen,” a column, in print and online, that celebrates

civilians who draw their guns in self-defense. The gunmaker has

never forgotten Ed Shultz’s attempt at compromise. “It almost

took down the company,” Debney told an interviewer in 2013. “We

won’t make that mistake again.”

In May, seventy thousand members of the N.R.A. convened in

Louisville for the organization’s annual meeting, which combines

elements of a trade show, a political convention, and Comic-Con.

When I arrived, I encountered a figure in a giant bird

costume—the mascot of the N.R.A.’s Eddie Eagle GunSafe program,

which teaches children up to fourth grade not to touch guns.

After that, the industry hopes they will become gun users. A

2011 report by the industry’s trade association urged the

creation of “hunting and target shooting recruitment programs

aimed at middle school level, or earlier.”

Cartoon

On a stage to one side, two men with guitars were performing

under a sign marked “N.R.A. Country,” a program that sponsors

musicians in order to attract younger members, a major industry

priority. The challenge is a “slow-motion demographic collapse,”

according to the Violence Policy Center, a gun-safety advocacy

group. Last year, Shooting Sports Retailer warned that “the

problem with failing to recruit and grow is that numbers equate

to political power.”

In Louisville, a giant banner promised “11 Acres of Guns and

Gear.” For kids, there were .22-calibre hand-guns designed to

look like military-issue sidearms. (In 2013, the magazine Junior

Shooters gave one to a thirteen-year-old reviewer, who raved

that it “looks cool and feels like a Beretta, which I think is

awesome.”) For sport shooters and survivalists, who talk about

TEOTWAWKI (“The end of the world as we know it”), there were

AR-15s, or “black rifles”—the civilian version of military

M-16s—which are known in the industry as the “Barbie doll of

guns,” because buyers keep coming back for new grips, sights,

and other mix-and-match accessories.

Much as the industry capitalized on the Los Angeles riots, it

has excelled, since 9/11, at tapping into the fear of terrorism.

Feldman, the former N.R.A. lobbyist, told me, “The threat is no

different on 9/12 than it was on 9/10, but the perception of it

changed dramatically. It is fear, but it’s not a fear that the

gun industry is promoting. It doesn’t have to.” Survivalist

fantasies about the breakdown of society “crossed over from

being the lunatic fringe to more serious after 9/11,” Feldman

said. “It’s not about the government coming after you. It’s

about terrorists taking out the electrical grid.”

In recent years, the gun industry’s product displays have become

so focussed on self-defense and “tactical” gear that some

hunters feel ignored. After a trade show in January, David E.

Petzal, a columnist for Field & Stream, mocked the “SEAL

wannabes,” and wrote that “you have to look fairly hard for

something designed to kill animals instead of people.” The

contempt is mutual; some concealed-carry activists call hunters

“Fudds,” as in Elmer.

The U.S. Concealed Carry Association had a large exhibit. Based

in Wisconsin, it promotes what it calls the “concealed-carry

lifestyle” and sells training materials and “self-defense

insurance,” which subsidizes legal fees for gun owners if they

shoot someone. Tim Schmidt, the founder, told me, “When I had

kids, I went through what I call my ‘self-defense awakening.’ ”

In 2004, he launched the magazine Concealed Carry and then

expanded. Members now receive daily e-mails urging them to buy

additional training and insurance, in case, as a recent e-mail

put it, “God forbid, the unthinkable should happen to you, and

you’re forced by some scumbag in a drug fueled rage to pull the

trigger.”

For several years, Schmidt had a sideline in packaging his sales

techniques. He calls the approach “tribal marketing.” It’s based

on generating revenue by emphasizing the boundaries of a

community. “We all have the NEED to BELONG,” he wrote in a

presentation entitled “How to Turn One of Mankind’s Deepest

Needs Into Cold, Hard CASH.” In a section called “How Do You

Create Belief & Belonging?,” he explained, “You can’t have a yin

without a yang. Must have an enemy.”

The meeting featured seminars, and one after another the

speakers encouraged attendees to be ready to fight. Kyle Lamb, a

former Delta Force operator, urged the mostly middle-aged crowd

to adopt a “combat mind-set.” He said, “Ten minutes from now, or

an hour from now, or two days from now, you may be in that

fight.” He said that we must prepare for the emotional

consequences, including “the sound people make when they get

shot.”

The biggest crowd turned up for Dave Grossman, a prolific author

who has taught psychology at West Point. In “On Combat” (2004),

he described society as populated by sheep, wolves, and

sheepdogs. “If you want to be a sheep, then you can be a sheep

and that is okay,” he wrote. “But you must understand the price

you pay. When the wolf comes, you and your loved ones are going

to die if there is not a sheepdog there to protect you.” The

concept went viral, inspiring T-shirts and a fictional scene in

“American Sniper,” the film based on the memoir of Chris Kyle,

in which Kyle’s father tells him to be a sheepdog, “blessed with

the gift of aggression.”

Grossman, who is friendly and intense in person—I discovered

later that he is a paid lecturer for Tim Schmidt’s group—gave

his audience the bleakest portrait of the future that I’ve

heard. He predicted that terrorists will detonate a nuclear

weapon on a boat off the coast of the United States, and that

they will send people infected with diseases—“suicide bio

bombers”—across the border from Mexico. Then he said, “I’ll tell

you what’s next, folks: school-bus and day-care massacres.”

Eventually, he wound his way to the solution: concealed carry.

“There is a time, in the first five to ten minutes in every one

of these events, when one or two well-trained people with a

concealed weapon can rise from the entire pack.” Americans,

Grossman told us, must accommodate to a future of “armed people

everywhere.”

Gerald Ung, the man who shot Edward DiDonato during an argument

on a Philadelphia street, didn’t buy a gun because he was

thinking of a “bio bomber.” In 2008, while he was in law school,

he moved to an unfamiliar neighborhood and heard about a girl

who was raped nearby and a classmate who had been robbed. He

remembered a statistic from the news that Philadelphia averaged

a murder a day. It seemed to him, he said later, that “kids were

just basically jumping people all the time.” Ung’s anecdotes

composed a chaotic portrait, and there was truth in

it—Philadelphia had one of the highest crime rates in

America—but they didn’t give him much context, and the city, in

fact, was safer than it had been in years. In 2008, major

crimes, including murder, rape, and aggravated assault, had

dropped to their lowest level since 1978. By 2009, murders were

down twenty-five per cent in three years. Ung’s sense of unease

was widespread. When crime rates were actually dropping, in the

mid-two-thousands, almost seventy per cent of Americans believed

that crime had risen in the previous year. Some studies of those

misperceptions blame a change in life style: as people drive

more, and have less contact with neighbors, they report a

greater fear of crime. Other studies focus on news reports that

give heavy attention to low-probability threats. An analysis of

Los Angeles television stations in 2009 found that local

broadcasts often started with crimes that were not even in Los

Angeles, leaving viewers with the impression that the biggest

thing happening most days is something awful. Frightening but

remote threats, such as shark attacks, which some scholars call

“fearsome risks,” throw off our judgment. Our instinct is to

respond with action—in Ung’s case, by carrying a gun.

Ung was charged with attempted murder and aggravated assault. He

went on trial on February 8, 2011. DiDonato remained in critical

condition for a month. After fourteen surgeries, he had regained

the ability to walk, but his left foot hung limp, and he

suffered lasting damage to his intestines.

In court, many of the participants from that night testified,

and it became clear that, in the seventy seconds in which the

encounter unfolded, each side had misread the intentions and

emotions of the other. Thomas Kelly, the reveller who had lunged

at Ung’s group, had misjudged the effect of his cursing and

gesturing. “It was more of a humorous ‘Fuck you,’ ” he said,

though Ung’s friend Joy Keh was convinced that Kelly and the

others were a “bloodthirsty gang.” Ung’s misreading may have

been the most catastrophic. When Kelly hiked up the drooping

belt of his pants, Ung suspected that he, too, might have a gun.

That mistake is not uncommon: a person holding a gun is more

likely to misperceive an object in another person’s hand to be a

gun, according to a 2012 study published in the Journal of

Experimental Psychology.

After a six-day trial, the jury acquitted Ung of all charges.

(“A victory for all of us,” a gun-rights blog declared.) In the

courtroom, Ung sobbed and clasped his hands in prayer. “Just get

me out of here,” he said, weeping, as he was led away by his

supporters, and he never said another word in public.

The centerpiece of the N.R.A. annual convention this year was

the endorsement of Donald Trump for President, the most

fervently pro-gun nominee in Presidential history. He has called

for a national right to concealed carry.

Trump and the N.R.A. were not always allies. In his book “The

America We Deserve,” published in 2000, Trump accused

Republicans of toeing “the N.R.A. line” by rejecting “even

limited restrictions.” He wrote of his support for a ban on

assault weapons and a seventy-two-hour waiting period on gun

purchases, both anathema in the gun-rights community. But as a

candidate Trump had abandoned those views, and he was forgiven:

at gun shows this year, venders have been selling olive-green

“Trump’s Army” T-shirts, alongside shirts in red and white,

lifeguard-style, marked “Waterboarding Instructor.” (Trump has

promised to resume the use of waterboarding.)

When Trump took the stage in Louisville, he said, “There are

thirteen million right-to-carry permit holders in the United

States. I happen to be one of them.” (He has a permit in New

York State; it’s not clear how often he has carried a gun.)

Trump can seem like the ultimate spokesman for the age of

concealed carry: the original “tribal marketer,” the man who

sees enemies everywhere. He reminded the audience of the

fourteen people who were killed in San Bernardino: “If we had

guns on the other side, it wouldn’t have been that way.” He made

a gun out of his thumb and forefinger, and said, “I would

have—boom!”

There was a time when the N.R.A. defined itself by conservative

free-market principles, but in recent years, as American incomes

have diverged, it has given greater emphasis to a populist line,

suggesting that powerful Americans are seeking to disarm and

endanger less privileged citizens. Before Trump took the stage,

the crowd watched a video about “political élites and

billionaires.” “The thought of average people owning firearms

makes them uncomfortable,” the narrator said. “They don’t like

how the men and women who build their office buildings, vacation

homes, and luxury cars, who mop their floors, clean their

clothes, and serve their dinner, have access to the same level

of protection as their armed security guards.” Alert to the

theme, Trump called on Hillary Clinton to give up her Secret

Service protection. “They should immediately disarm,” he said.

“And let’s see how good they do.” He promised his audience,

“We’re going to bring it back to a real place, where we don’t

have to be so frightened.”

Having an enemy is also part of N.R.A. strategy, according to

Feldman, the former lobbyist. During George W. Bush’s

Presidency, when the threat of gun control receded, membership

dropped, he said. (The group declines to confirm that.)

“Negatives are so much more powerful than positives in

politics,” he told me. “I can get people all fired up about

something that takes something away. Even if you don’t own one

of these guns, if they’re going to take one away from you, all

of a sudden I want to buy one.” In writing mailings to members,

Feldman emphasized the threat posed by Americans who support gun

control. He gave me a hypothetical example: “ ‘If you can’t send

us twenty-two dollars and fifteen cents by the close of business

Friday, the lights on your cherished Second Amendment freedoms

will dim forever.’ I mean, I can go on, but that’s your standard

fund-raising shtick.”

For all the bluster, in two days at the convention I encountered

few members of the rank and file who actually believed it. Many

were wary of the hucksterism, the bravado, the odes to the

“sheepdog.” “Even if you’re going to intervene, it should never

be with a gun first,” Lowell Huckelberry, a concealed carrier

and retired businessman from southern Illinois, told me. When I

asked people, as I did dozens of times this spring, why they

chose to carry, most attributed it to a compounding sense of

vulnerability, a suspicion that spectacular displays of violence

signal a breakdown of public morality and the state’s ability to

provide security. “We had a recent mall shooting,” Rachel Keith,

a forty-six-year-old woman who has been carrying for six years,

told me. In response, she taught her daughters to scout for

exits in public places, and enrolled them in pistol classes so

that they will “be confident that they, too, can work a gun.”

Armed citizenship generates its own momentum. Sid O’Nan, a

genial and self-effacing father of two teen-agers, who works as

an I.T. specialist for the Department of Agriculture, told me

that, growing up, he had done some hunting, but not much. Yet in

recent years he saw more guns around. “As I would invite buddies

over, they would always have handguns,” he said. He now carries

a Glock 17. The notion that more firearms reduces the risks

posed by more firearms is paradoxical to some and reassuring to

others. I asked O’Nan what he meant when he said that times had

changed. “I just see all the garbage that’s going on, and I

thought, You know what? I couldn’t live with myself if I

couldn’t be there to protect my family,” he said. “I don’t know

firearms. I don’t know ballistics. I don’t know holsters. I’m

just trying to glean from a friend what he says. I’ve asked him,

‘Should I go for the head if somebody has full-body armor?’ He

says, ‘No, just center mass. Your 9-mm. will knock them to the

ground, and you can get the heck out of there.’ ”

At the heart of the concealed-carry phenomenon is a delicate

question: Does it save lives?

Last month, I called David Jackson, a thirty-two-year-old truck

driver in Columbia, South Carolina. He has six children. On

January 26th, he was getting a haircut at Next Up Barber and

Beauty, accompanied by his girlfriend and two youngest sons,

ages two and four, when a pair of men in masks and hoodies came

in the front door. One pumped a shotgun and said, “You already

know what this is.” The other waved a handgun, and started

moving down the line of chairs, demanding wallets and cash, and

reaching into the barbers’ pockets.

A surveillance camera recorded what happened next. When the

robber with the handgun had his back turned, Jackson reached

under his plastic salon smock, pulled out a .357 Magnum—he had

obtained his license six months earlier—and fired. It happened

that one of the barbers, Elmurray Bookman, was also licensed to

carry. Bookman pulled out his gun, and, together, he and Jackson

fired at the robber, who tumbled out of the back door, collapsed

on the sidewalk, and died of multiple gunshot wounds.

Jackson turned to the front of the shop, where the first robber

was fleeing through the door. Jackson fired three more bullets

but missed, and the robber escaped. When the police arrived,

they watched the footage, took down Jackson’s statement, and

ruled the shootings self-defense. It was a one-day story on the

local news. Jackson returned to work the following Monday.

When the gun industry talks about concealed carry, it highlights

experiences like Jackson’s. But he was no ordinary shooter: he

spent two years in the Air Force, where he trained for hundreds

of hours. Later, he erected targets behind his home so that he

could practice. (Gerald Ung visited a gun range on three or four

occasions.) When I spoke to Jackson, he was in the cab of his

truck. I asked how he felt about the experience. “Terrible,” he

said. He wouldn’t change his decision to shoot, but it had

shaken him. “I don’t feel good. You know, kind of sick about it.

A lot of times, you know, you close your eyes to go to sleep and

you think about it. I can see everything that happened, and

then, right before the shots go off, I wake up. I jump.”

I asked Jackson why he had obtained a permit. “I thought it was

going to be more an ISIS thing, or something,” he said. “I never

thought I’d need to use it like that.” I asked how his kids were

doing. “They’re like kind of obsessed with guns now. Especially

my four-year-old. He’s like, ‘My daddy shot the robber!’ That’s

what he always says. The other day, he asked me, ‘Daddy, could

you teach me?’ I was like, ‘Teach you what?’ ‘How to shoot.’ I

told him when he turns five I’ll start teaching him.”

In the early years of concealed carry, there was a debate about

whether it reduced violence or increased it. A decade ago, when

mass shootings were emerging as a frequent phenomenon, the

conservative economist John Lott asserted that carry guns could

halt those killings—a precursor to the N.R.A.’s current maxim

that “the only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good

guy with a gun.” It’s a mantra among concealed carriers, but

evidence is sparse. A 2014 study by the F.B.I. found that, in a

hundred and sixty “active shooter” incidents from 2000 to 2013,

armed citizens who were not security guards stopped the “bad

guy” on one occasion (when a patron shot an attacker at the

Players Bar and Grill, in Winnemucca, Nevada, in 2008). Unarmed

citizens, by contrast, stopped active shooters on twenty-one

occasions. In recent years, scholars have found that concealed

carry may be altering society in measurable, and unwelcome,

ways: in 2014, a study led by the Stanford law professor John J.

Donohue III examined the effect of concealed-carry laws on

crime, using data from 1979 to 2010. He found that the laws led

to “substantially higher rates” of aggravated assault, rape,

robbery, and murder.

For the past decade, the most reliable business in Gun Valley

has been concealed carry. But, nearly a century after Jonathan

Mossberg’s family began to profit from the gun business, he is

betting that this is about to change.

On a warm morning in northern Connecticut, Mossberg brought me

to a private shooting club. He was wearing loafers, khakis, and

a blue-and-white oxford shirt. O. F. Mossberg & Sons, founded in

1919 by Jonathan’s great-grandfather, is one of the world’s

largest makers of shotguns. When he was sixteen, Jonathan

started work at the company, and by the time he left, in 2000,

he was vice-president of acquisitions.

He took a twelve-gauge shotgun from a long black plastic case.

Sixteen years after Ed Shultz’s attempt to build a smart gun all

but drove him into hiding, Mossberg thinks that times have

changed. His invention, which he calls the iGun, is synched to a

ring that he wears on his right hand. “You don’t swipe it,” he

said. “You don’t do a retina scan or anything like that.” He

loaded three shells, put the gun to his shoulder, and fired

three rounds toward the far end of a trap-shooting range. He put

the gun on his other shoulder, and said, “Left hand, no ring.”

He pulled the trigger and nothing happened.

Mossberg first started talking publicly about his smart gun last

year, and he braced for hate mail. Officially, the N.R.A. does

not oppose the development of smart-gun technology, but it

frames the idea as fanciful or dangerous. (On its Web site, it

says that the government would exploit the technology to “allow

guns to be disabled remotely.”) “But I got literally almost no

hate mail,” Mossberg said. “I got maybe three negative ones.”

Mossberg hopes to get his technology into a handgun—and then get

the gun into the hands of prison guards, air marshals, and

parents. An ordinary Mossberg shotgun sells for about three

hundred and fifty dollars. He figures that his gun will cost up

to two hundred dollars more. “I get e-mails every day. ‘Where

can I buy it? What’s your stock symbol?’ I answer them all very

politely. ‘We’re trying to raise money.’ ” The big gun companies

aren’t interested. “They’re doing so well now that they really

don’t have to care.” No C.E.O. wants to be the next Ed Shultz,

and ever since the 2005 law immunized gunmakers against lawsuits

they have little incentive to develop new ways of reducing

accidents or misuse.

Many smart-gun advocates believe that the only way the guns will

become available is if military and police agencies agree to buy

them, which would spur companies to invest in the technology. In

April, the Obama Administration announced that the Justice and

Homeland Security departments are preparing standards that smart

guns will need to meet for government contracts. Valerie

Jarrett, a senior adviser to the President who is in charge of

the project, told me that it had a personal relevance. “My

grandfather was shot and killed with his own handgun,” she said.

“He was a dentist here in D.C. He was an avid hunter. He kept a

gun in his office, because, as a dentist, he kept opiates in his

office. One day, two people broke in and pulled out a toy gun.

He pulled out the real gun and they proceeded to take his real

gun away from him and shoot and kill him.” She went on, “We’re

not saying that smart-gun technology is going to save every

life. But, if it saves a few, why wouldn’t we take those steps?”

A smart gun would not prevent most gun deaths, but it could have

a powerful effect on six hundred or so accidental gun deaths

each year—including an average of sixty-two, each year, that

kill children under fourteen. During one week in April, four

toddlers shot and killed themselves. Another, a two-year-old

boy, found a gun on the floor of a car and shot through the back

of the driver’s seat, killing his mother. The statistical story

of American gun violence is less about “active shooters” and

“sheepdogs” than about impulses and cruelties of fate.

The chances of being killed by a mass shooter are lower than the

chances of being struck by lightning, or of dying from

tuberculosis. The chance of a homicide by a firearm in the home

nearly doubles the moment that a firearm crosses the threshold.

Dave Grossman’s vision of “armed people everywhere” has a

seductive certainty, but having a gun at hand alters the

chemistry of ordinary life—the arguments, the miscalculations,

the perceptions of those around us.

If the American gun business stays on its present course, its

market will likely continue to consolidate into the hands of a

smaller, more dedicated community. That will widen the gap

between those with a “combat mind-set” and those without,

between “friends” and “enemies.” If Donald Trump reaches the

White House, he will bring with him a moral logic of concealed

carry. If he falls short of the Presidency, his admirers will

have gained, at a minimum, fresh evidence of their encirclement.

As the pro-gun and the anti-gun worlds grow further apart, it

gets harder for each side to understand the intentions of the

other. They are, more than ever, like two groups squaring off in

the dark, convinced that the other wishes them harm. |