The Fable of

the Sick Anti-Vaxxer

|

| In the early 20th century,

a famous anti-vaxxer exposed himself to smallpox. What happened

next offers a COVID cautionary tale. |

| |

| By Rebecca Onion |

Slate |

| |

A

parishioner of Los Angeles’ Hillsong Church dies of COVID-19

after making anti-vax jokes on Facebook and Instagram, some of

which were posted from his hospital bed; after his death, the

founder of the church tells CNN that vaccines are a “personal

decision.” A Nashville radio host who had voiced skepticism

about the COVID vaccine gets the disease and, after suffering

from COVID-related pneumonia, goes on a ventilator; his brother

tells the media, “If he had to do it over again, he would be

more adamantly pro-vaccination.” Another pastor, from Texas,

speaks publicly about his regret at not getting vaccinated

before getting COVID and going to the intensive care unit: “I

recognized that I had been a bit cavalier.”

This was a week for these kinds of stories to circulate, as the

delta variant has surged and it became clear that, as the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Dr. Rochelle

Walensky said at the White House, “this is becoming a pandemic

of the unvaccinated.” These stories, which I’ve come to think of

as Fables of the Sick Anti-Vaxxer, are familiar from past

battles over vaccination. There’s a 1975 poster, created by the

World Health Organization in service of worldwide childhood

vaccination campaigns, that epitomizes health authorities’

belief in the power of this kind of morality tale. The poster

features two mothers, one who vaccinates her baby, one who

doesn’t. After an epidemic strikes, sparing the vaccinated baby,

the vaccine-hesitant mother, standing over a little bed, begs

the health worker: “Is it too late to vaccinate?” The health

worker, walking away, says (harshly!) “Yes, it is!” as the

mother weeps over the little bed.

Andrea Kitta, who studies vaccination folklore, suggests that

the fable has diverse social functions. It cements the in-group

of the vaccinated, providing the vaccinated reader with

confirmation that their choice was the right one. Jonathan

Berman, author of Anti-Vaxxers: How to Challenge a Misinformed

Movement, said that the fable allows the vaccinated some

“choice-supportive bias/post-purchase rationalization,” pointing

out that “people will look up reviews of cars they’ve already

bought or vacation destinations they’ve already been to because

they want to reassure themselves that they made the right

choice”—this may be similar. It’s also delicious for vaccinated

people to see the unvaccinated finally realizing that they were

wrong and being forced to acknowledge a shared reality—something

that’s been hard to come by in the Trump years. Kitta told me

about a meme she saw recently that embellished on the saying

“You can’t fix stupid” with a picture of the coronavirus, next

to a speech bubble: “Well, I can!” (“Kind of a rough one there,”

Kitta added.)

There’s often a certain meanness to the circulation of these

stories. Responses to a tweet about a 31-year-old anti-vax

father on a ventilator in Missouri saying goodbye to his

6-year-old son were unsympathetic—even though this story, like

many others, featured the man’s avowed desire to get the vaccine

if he recovers. “They should be sent home with a religious book

of their choice,” one replier said. “If only there were

scientific evidence at how bad this virus is and what it can do

to you…oh wait,” another snarked. “Here is how much I am

concerned for someone that had 18 MONTHS of warnings, plus a

chance for the vaccine: I really want tacos,” another joked.

But what about any onlookers among the hesitant? Might these

stories be serving a different function for them? A media circus

from the American smallpox outbreaks of the early 20th century

is an object lesson in the way this fable does, and doesn’t,

convince anyone to change their position on vaccination. During

this time, many people resisted compulsory vaccination against

smallpox, because they were (justifiably, in some cases) afraid

of the quality of the vaccines, unwilling to miss the week of

work to suffer through the vaccine reaction, resistant to

government compulsion, or all three. As historian Michael

Willrich points out, this was a period where newspapers often

featured Fables of the Sick Anti-Vaxxer. The New York Times

reported on one such death by writing that the person in

question had “died of the disease he defied,” and editorialized,

when an epidemic broke out among anti-vaccinationists in Zion

City, Illinois, in 1904: “There is likely to be an excellent,

though rather dangerous, opportunity to see what can be done

with a disease of that sort by the exercise of ‘faith.’ ”

The center of the most memorable media frenzy of this type was

Immanuel Pfeiffer. In retelling his story, I am relying on an

account of it in Karen Walloch’s book The Antivaccine Heresy.

Pfeiffer was a burr in the side of Boston’s public health

authorities. He ran a magazine, Our Home Rights, that railed

against compulsory vaccination (while advancing other

Progressive Era causes like pacifism and vegetarianism), and he

spoke on the topic in “every public forum he could find,” as

Walloch writes. Pfeiffer was publicity-stunt-friendly, having

fasted for weeks on two occasions as a way to attract people to

his medical practice. He had a medical license, but participated

in many fringe-y practices, like using hypnotism on his patients

and “treating” people by mail.

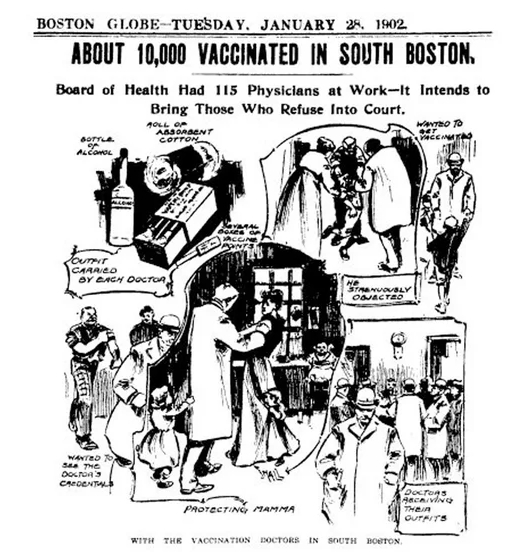

Annoyed to death by Pfeiffer as smallpox hit the city, Samuel

Holmes Durgin, the chairman of the Boston Board of Health, dared

the doctor to expose himself to smallpox, unvaccinated. Durgin

had said publicly of Pfeiffer: “I have no patience with those

who say vaccination is useless and harmful. … I wish the

smallpox would get into their ranks instead of among innocent

people.” In early 1902, Durgin invited “the adult and leading

members of the anti-vaccinationists” to “a grand opportunity” to

test their beliefs publicly by inspecting sick patients

personally. Pfeiffer said he’d do it. He visited a smallpox

isolation hospital on Gallops Island and examined patients

during a tour, then slipped away, taking public transportation

home, and attending a public meeting at a church.

Thirteen days later, just about the amount of time it takes to

incubate a case of smallpox, Pfeiffer vanished from public view.

Durgin, questioned by reporters about whether his bet had been

ill-advised, defended himself by saying that he had assigned a

policeman to tail Pfeiffer and make sure that if he got

smallpox, he wouldn’t come in contact with the public. The press

was on the case, and police detectives were dispatched to find

him. When health authorities finally located him, at his family

farm in Bedford, Massachusetts, Pfeiffer’s smallpox was,

according to the doctor assigned to examine him, “fully

developed.”

The press, Walloch writes, “exploded with articles and

editorials about his illness.” The story made it into the New

York Times, the Boston Globe, and many medical journals. “The

victim of his own folly and professional vanity,” the Boston

Herald editorialized under the front-page headline

“Anti-Vaccinationist May Not Live.” This was an excellent story,

and the health authorities knew it; one, Pfeiffer said, even

tried to take a picture of his face, covered in pustules,

presumably with the intention of getting it to the press. (His

physician intervened.)

And yes—Pfeiffer lived. Not only that, he refused even to

acknowledge that the experience had been a negative one, saying

“the disease of smallpox, dreadful as it is said to be, never

caused me pain for one minute.” And he still wouldn’t admit that

vaccines worked. He said that the reason he got the disease

wasn’t because he was unvaccinated, but because he was

“immensely overworked” and exhausted. He even refused to

acknowledge that his neighbors were angry at him for going

through with the stunt, instead saying that they were only mad

that the vaccines they rushed out to get upon learning that he

had smallpox had made them sick.

And so even this extreme example of the Fable of the Sick Anti-Vaxxer

didn’t seem to have the effect authorities thought it would. The

day after this fable hit the press, the health department made a

vaccination sweep through Boston and “met with but little

objection”; “the case of Dr. Pfeiffer had helped their cause

immediately.” Medical journals argued that the case had been an

“object lesson” that had helped the cause of vaccination. But

when the vaccinators went back to knocking on doors a couple of

weeks later, after the public learned about Pfeiffer’s survival,

they had less luck. And other anti-vaccinationists refused to

acknowledge this episode as a blow to their cause, saying that

this was just one anecdote, that Durgin should have been more

careful, and that the childhood vaccination Pfeiffer had 60

years prior meant that he actually was immunized, and therefore

his illness was proof that vaccination didn’t work. In the end,

Walloch argues, the episode was not quite the magic bullet of

persuasion that Durgin hoped for. Even the anti-vaxxer’s

sickness meant different things to different people.

In his book, Berman categorizes anti-anti-vaccination persuasion

tactics in three ways: “reactive” (think mean-spirited arguments

with anti-vaxxers); “information-deficit” (dumping info on

people); and “community-based” (tactics that demonstrate that

other people around anti-vaxxers are vaccinating, “taking into

consideration their self-identity and values”). These lessons,

taken from research done around vaccination drives conducted in

service of childhood vaccines, may or may not translate to our

current situation. But I think it’s clear that these new fables

will only be as useful as we let them. It’s difficult to be

kind, when our fragile hopes for some post-pandemic normalcy

seem to be falling apart due to other people’s refusal to get

vaccinated. But the Fable of the Sick Anti-Vaxxer—a story aimed

at the hesitant, from somebody who once thought as they did—may

work best when we, the vaccinated, just let it sit, and resist

the temptation to gloat. |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|