|

The

workers at the Standard Oil Refinery in New Jersey, gave the

building that name, waving goodbye to their colleagues when they

entered the shadowed opening, promising to have undertakers

waiting when they came out. The building was only one year old,

that fall of 1924, but it had earned the nickname. The

workers at the Standard Oil Refinery in New Jersey, gave the

building that name, waving goodbye to their colleagues when they

entered the shadowed opening, promising to have undertakers

waiting when they came out. The building was only one year old,

that fall of 1924, but it had earned the nickname.

It looked harmless enough from the outside, the usual style of

factory buildings on the New Jersey site, the familiar rectangle

of neat red brick with narrow windows set in stone. Inside, the

first impression was also of routine, noise and heat, the hiss

and clank of the pipes, the grumble and clatter of the retorts.

And then the unfamiliar, a smell carried by vapors rising from

the machinery, not the usual odor of gasoline, but the dull

musty scent of tetraethyl lead.

Five years earlier, a chemical engineer working for General

Motors had discovered that tetraethyl lead cured a stubborn

knocking problem in the car engines. Even GM’s best cars, its

elegant Cadillacs, banged so loudly under the hood that

customers worried that the engines were breaking apart. The

noise was a natural byproduct of the engine’s design in which

gasoline tended to mix with air, heat, spontaneously ignite and

explode, sometimes loudly enough to startle a driver into losing

control.

Tetraethyl lead – or TEL as the industrial shorthand referred to

it – solved that problem. As we know now – or, more accurately,

have known for decades now – it caused many more. But what most

people don’t know – and what I didn’t learn until I started

researching the toxicology of the early 20th century – is that

scientists warned of, and tried to prevent, those lead-based

problems back in the 1920s. Their evidence was, in fact, so

solid that that some cities, like New York, attempted to block

its use. They were overruled by a federal government that

preferred to ally itself with major corporations. A cautionary

tale, you might say, although not a lesson we’ve followed with

any notable consistency.

Tetraethyl lead was nothing new back then; it was actually a

19th century discovery from European laboratories. But that

innovative GM engineer, one Thomas Midgley, Jr., put it to a new

use. (Midgley would later become notorious among

environmentalists for his contribution not only to leaded

gasoline but to the worldwide use of chlorofluorocarbons).

Midgley was working under the direction of GM research head

Charles Kettering when he made his key discovery regarding those

knocking engines: tetraethyl lead (a chemical blending of lead,

carbon and hydrogen) bonded with the fuel, enveloping it into a

happily non-explosive material.

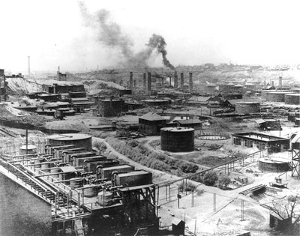

Both the automobile and the oil industry took instantly to

Midgley’s anti-knock solution, pouring money into production facilities, advertising its wonders. One of the earliest

factories to make the additive was the Standard Oil facility in

Bayway, New Jersey. And it was there, in the loony gas building,

that the warning signs became obvious.

facilities, advertising its wonders. One of the earliest

factories to make the additive was the Standard Oil facility in

Bayway, New Jersey. And it was there, in the loony gas building,

that the warning signs became obvious.

In the twelve months since the company had begun making the

anti-knock ingredient, plant laborers’ fear of the place had

steadily increased. The men who worked in the TEL building, in

the clanking heat and drifting vapors, had become increasingly

odd – moody, short-tempered, unable to sleep. Some of the

workers started getting lost on the familiar plant grounds, had

trouble even remembering their friends. And then, in October of

1924, laborers from that same building started collapsing, going

into convulsions, babbling deliriously. By the end of September,

32 of the 49 TEL workers were in the hospital and five of them

died.

Standard Oil issued a coolly dismissive response: “These men

probably went insane because they worked too hard,” the building

manager told The New York Times. Those who didn’t survive had

merely worked themselves to death, he continued, due to

enthusiasm for the job.

Other than that, the company didn’t really see a problem at all.

The Standard Oil explanation failed to impress the state of New

Jersey. It ordered the plant closed. The local district attorney

wasn’t impressed either. He called the chief medical examiner

from New York City, Charles Norris, and asked if his innovative

chemistry division could do some research into the compound.

Norris was happy to do so. He hadn’t liked Standard Oil’s

position either. He decided, in fact, to issue his own

statement, contradicting the industry’s perspective on TEL in

explicit terms: “The fact that it is readily absorbed and highly

poisonous was discovered in Germany about 1854 when tetraethyl

lead was discovered, and it has not been used in industry during

most of its seventy years since then because of its known

deadliness.”

Investigators discovered that before the illnesses at Standard

Oil, another TEL processor, the DuPont Company, had lost two

workers at its Dayton, Ohio plant. They had died from lead

poisoning. Lead was well known, as Norris emphasized, for its

tendency to damage the nervous system. And lead-laced vapors,

like those emitted in TEL manufacturing, absorbed through the

skin and were inhaled directly into the lungs.

It turned out, in fact, that months before the New Jersey

workers died, several of the supervisors at the loony gas

building had recommended that the production be shut down.

They’d become alarmed themselves by the way the increasingly

bizarre behavior of the workers and by the signs of obvious

illness.

Standard Oil did not back down. In answer to this new round of

criticisms, the company organized a press conference at its

Manhattan offices (not in New Jersey, of course), featuring the

developer of tetraethyl lead himself. Midgley assured reporters

that handled properly there was nothing dangerous about his

prized discovery. To prove it, he washed his hands in a bowl

filled with TEL. “I’m taking no chances whatever,” he said. “Nor

would I take any chances by doing that every day.”

Like Standard Oil executives, he blamed the workers, both at

Dupont and at the New Jersey plant, for failing to protect

themselves properly. Gloves and masks had been available at the

refinery; it was the workers’ responsibility to wear them. But

they weren’t well educated men, a company vice president

explained to the reporters, and perhaps the employees hadn’t

realized that working with TEL was “man’s work”, with all the

risks implied.

He was right, of course, that the loony gas workers didn’t know

what the risks were. But neither – even at that moment – did he. |