Against his better judgment

|

| In the meth corridor of Iowa, a federal

judge comes face to face with the reality of congressionally

mandated sentencing |

| By Eli Saslow |

The Washington Post |

| |

They filtered into the courtroom and waited

for the arrival of the judge, anxious to hear what he would

decide. The defendant’s family knelt in the gallery to pray for

a lenient sentence. A lawyer paced the entryway and rehearsed

his final argument. The defendant reached into the pocket of his

orange jumpsuit and pulled out a crumpled note he had written to

the judge the night before: “Please, you have all the power,” it

read. “Just try and be merciful.” They filtered into the courtroom and waited

for the arrival of the judge, anxious to hear what he would

decide. The defendant’s family knelt in the gallery to pray for

a lenient sentence. A lawyer paced the entryway and rehearsed

his final argument. The defendant reached into the pocket of his

orange jumpsuit and pulled out a crumpled note he had written to

the judge the night before: “Please, you have all the power,” it

read. “Just try and be merciful.”

U.S. District Judge Mark Bennett entered and everyone stood. He

sat and then they sat. “Another hard one,” he said, and the room

fell silent. He was one of 670 federal district judges in the

United States, appointed for life by a president and confirmed

by the Senate, and he had taken an oath to “administer justice”

in each case he heard. Now he read the sentencing documents at

his bench and punched numbers into an oversize calculator. When

he finally looked up, he raised his hands together in the air as

if his wrists were handcuffed, and then he repeated the

conclusion that had come to define so much about his career.

“My hands are tied on your sentence,” he said. “I’m sorry. This

isn’t up to me.”

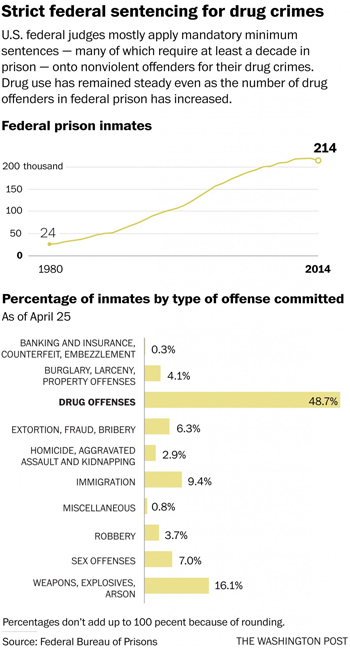

How many times had he issued judgments that were not his own?

How often had he apologized to defendants who had come to

apologize to him? For more than two decades as a federal judge,

Bennett had often viewed his job as less about presiding than

abiding by dozens of mandatory minimum sentences established by

Congress in the late 1980s for federal offenses. Those mandatory

penalties, many of which require at least a decade in prison for

drug offenses, took discretion away from judges and fueled an

unprecedented rise in prison populations, from 24,000 federal

inmates in 1980 to more than 208,000 last year. Half of those

inmates are nonviolent drug offenders. Federal prisons are

overcrowded by 37 percent. The Justice Department recently

called mass imprisonment a “budgetary nightmare” and a “growing

and historic crisis.”

Politicians as disparate as President Obama and Sen. Rand Paul

(R-Ky.) are pushing new legislation in Congress to weaken

mandatory minimums, but neither has persuaded Sen. Charles E.

Grassley (R-Iowa), who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee

that is responsible for holding initial votes on sentencing

laws. Even as Obama has begun granting clemency to a small

number of drug offenders, calling their sentences “outdated,”

Grassley continues to credit strict sentencing with helping

reduce violent crime by half in the past 25 years, and he has

denounced the new proposals in a succession of speeches to

Congress. “Mandatory minimum sentences play a vital role,” he

told Congress again last month.

But back in Grassley’s home state, in Iowa’s busiest federal

court, the judge who has handed down so many of those sentences

has concluded something else about the legacy of his work.

“Unjust and ineffective,” he wrote in one sentencing opinion.

“Gut-wrenching,” he wrote in another. “Prisons filled, families

divided, communities devastated,” he wrote in a third.

And now it was another Tuesday in Sioux City — five hearings

listed on his docket, five more nonviolent offenders whose cases

involved mandatory minimums of anywhere from five to 20 years

without the possibility of release. Here in the methamphetamine

corridor of middle America, Bennett averaged seven times as many

cases each year as a federal judge in New York City or

Washington. He had sentenced two convicted murderers to death

and several drug cartel bosses to life in prison, but many of

his defendants were addicts who had become middling dealers,

people who sometimes sounded to him less like perpetrators than

victims in the case reports now piled high on his bench.

“History of family addiction.” “Mild mental retardation.” “PTSD

after suffering multiple rapes.” “Victim of sexual abuse.”

“Temporarily homeless.” “Heavy user since age 14.”

Bennett tried to forget the details of each case as soon as he

issued a sentence. “You either drain the bathtub, or the guilt

and sadness just overwhelms you,” he said once, in his chambers,

but what he couldn’t forget was the total, more than 1,100

nonviolent offenders and counting to whom he had given mandatory

minimum sentences he often considered unjust. That meant more

than $200 million in taxpayer money he thought had been

misspent. It meant a generation of rural Iowa drug addicts he

had institutionalized. So he had begun traveling to dozens of

prisons across the country to visit people he had sentenced,

answering their legal questions and accompanying them to drug

treatment classes, because if he couldn’t always fulfill his

intention of justice from the bench, then at least he could

offer empathy. He could look at defendants during their

sentencing hearings and give them the dignity of saying exactly

what he thought.

“Congress has tied my hands,” he told one defendant now.

“We are just going to be warehousing you,” he told another.

“I have to uphold the law whether I agree with it or not,” he

said a few minutes later.

The courtroom emptied and then filled, emptied and then filled,

until Bennett’s back stiffened and his robe twisted around his

blue jeans. He was 65 years old, with uncombed hair, a relaxed

posture and a midwestern unpretentiousness. “Let’s keep moving,”

he said, and then in came his fourth case of the day, another

methamphetamine addict facing his first federal drug charge, a

defendant Bennett had been thinking about all week.

His name was Mark Weller. He was 28 years old. He had pleaded

guilty to two counts of distributing methamphetamine in his home

town of Denison, Iowa, which meant his mandatory minimum

sentence as established by Congress was 10 years in prison. His

maximum sentence was life without parole. For four months, he

had been awaiting his hearing while locked in a cell at the Fort

Dodge Correctional Facility, where there was nothing to do but

watch Fox News on TV, think over his life and write letters to

people who usually didn’t write back.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve asked myself, ‘How did I

get into the situation I’m in today?’ ” he had written.

Marijuana starting at age 12. Whiskey at 14. Cocaine at 16, and

methamphetamine a few months later. “Always hooked on something”

was how some family members described him in the pre-sentencing

report, but for a while he had managed to hold his life

together. He graduated from high school, married, had a daughter

and worked for six years at a pork slaughterhouse, becoming a

union steward and earning $18 an hour. He bought a doublewide

trailer and a Harley, and he tattooed the names of his wife and

daughter onto his shoulder. But then his wife met a man on the

Internet and moved with their daughter to Missouri, and Weller

started drinking some mornings before work. Soon he had lost his

job, lost custody of his daughter and, in his own accounting,

lost his “morals along with all self control.” He started

spending as much as $200 each day on meth, selling off his

Harley, his trailer and then selling meth, too. He traded meth

to pay for his sister’s rent, for a used car, for gas money and

then for an unregistered rifle, which was still in his car when

he was pulled over with 223 grams of methamphetamine last year. something”

was how some family members described him in the pre-sentencing

report, but for a while he had managed to hold his life

together. He graduated from high school, married, had a daughter

and worked for six years at a pork slaughterhouse, becoming a

union steward and earning $18 an hour. He bought a doublewide

trailer and a Harley, and he tattooed the names of his wife and

daughter onto his shoulder. But then his wife met a man on the

Internet and moved with their daughter to Missouri, and Weller

started drinking some mornings before work. Soon he had lost his

job, lost custody of his daughter and, in his own accounting,

lost his “morals along with all self control.” He started

spending as much as $200 each day on meth, selling off his

Harley, his trailer and then selling meth, too. He traded meth

to pay for his sister’s rent, for a used car, for gas money and

then for an unregistered rifle, which was still in his car when

he was pulled over with 223 grams of methamphetamine last year.

He was arrested and charged with a federal offense because he

had been trafficking methamphetamine across state lines. Then he

met for the first time with his public defender, considered one

of the state’s best, Brad Hansen.

“How much is my bond?” Weller remembered asking that day.

“There is no bond in federal court,” Hansen told him.

“Then how many days until I get out?” Weller asked.

“We’re not just talking about days,” Hansen said, and so he

began to explain the severity of a criminal charge in the

federal system, in which all offenders are required to serve at

least 85 percent of whatever sentence they receive. Weller

didn’t yet know that a series of witnesses, hoping to escape

their own mandatory minimum drug sentences, had informed the

government that Weller had dealt 2.5 kilograms of

methamphetamine over the course of eight months. He didn’t yet

know that 2.5 kilograms was just barely enough for a mandatory

minimum of 10 years, even for a first offense. He didn’t know

that, after he pleaded guilty, the judge would receive a

pre-sentencing report in which his case would be reduced to a

series of calculations in the controversial math of federal

sentencing.

“Victim impact: There is no identifiable victim.”

“Criminal history: Minimal.”

“Cost of imprisonment: $2,440.97 per month.”

“Guideline sentence: 151 to 188 months.”

What Weller knew — the only thing he knew — was the version of

sentencing he had seen so many times on prime-time TV. He would

have a legal right to speak in court. The court would have an

obligation to listen. He asked his family to send testimonials

about his character to the courthouse, believing his sentence

would depend not only on Congress or on a calculator but also on

another person, a judge.

The night before Weller’s hearing, Bennett returned to a home

overlooking Sioux City and carried the pre-sentencing report to

a recliner in his living room. He already had been through it

twice, but he wanted to read it again. He put on glasses, poured

a glass of wine and began with the letters.

“He was doing fine with his life, it seems, until his wife met

another man on-line,” Weller’s father had written.

“After she left, the life was sucked out of him,” his sister had

written.

“Broken is the only word,” his brother had written. “Meth sunk

its dirty little fingers into him.”

“I hope this can explain how a child was set up for a fall in

his life,” his mother had written, in the last letter and the

longest one of all. “Growing up, all he pretty much had was an

alcoholic mother who was manic depressive and schizophrenic.

When I wasn’t cutting myself, I was getting drunk and beating

the hell out of him in the middle of the night. When I wasn’t

doing all that I was trying to kill myself and ending up in a

mental hospital. Can you imagine being a four year old and

getting beat up one day and having to go visit that same person

in a mental hospital the next? No heat in the house, no lights,

nothing. That was his starting point.”

Bennett set down the report, stood from his chair and paced

across a room decorated with photos of his own daughter, in the

house that had been her starting point. There were scrapbooks

made to commemorate each year of her life. There were videotapes

of her high school tennis matches and photos of her recent

graduation from a private college near Chicago.

He had decided to become a judge just a few months after her

birth, in the early 1990s. His wife had been expecting twins, a

boy and a girl, and had gone into labor several months

prematurely. Their daughter had survived, but their son had died

when he was eight hours old, and the capriciousness of that

tragedy had left him searching for order, for a life of

deliberation and fairness. He had quit private practice and

devoted himself to the judges’ oath of providing justice, first

as a magistrate judge and then as a Bill Clinton appointee to

the federal bench, going into his chambers to work six days each

week.

Since then he had sent more than 4,000 people to federal prison,

and he thought most of them had deserved at least some time in

jail. There were meth addicts who promised to seek treatment but

then showed up again in court as robbers or dealers. There were

rapists and child pornographers that expressed little or no

remorse. He had installed chains and bolts on the courtroom

floor to restrain the most violent defendants. One of those had

threatened to murder his family, which meant his daughter had

spent her first three months of high school being shadowed by a

U.S. marshal. “It is a view of humanity that can become

disillusioning,” he said, and sometimes he thought that it

required work to retain a sense of compassion.

Once, on the way to a family vacation, he had dropped his wife

and daughter off at a shopping mall and detoured by himself to

visit the prison in Marion, Ill., then the highest-security

penitentiary in the country. He scheduled a tour with the

warden, and at the end of the tour Bennett asked for a favor.

Was there an empty cell where he could spend a few minutes

alone? The warden led him to solitary confinement, where

prisoners spent 23 hours each day in their cells, and he locked

Bennett inside a unit about the size of a walk-in closet.

Bennett sat on the concrete bed, ran his hands against the walls

and listened to the hum of the fluorescent light. He imagined

the minutes stretching into days and the days extending into

years, and by the time the warden returned with the key

Bennett’s mouth was dry and his hands were clammy, and he

couldn’t wait to be back at the mall.

“Hell on earth,” he said, explaining what just five minutes as a

visitor in a federal penitentiary could feel like, and he tried

to recall those minutes each time he delivered a sentence. He

often gave violent offenders more prison time than the

government recommended. He had a reputation for harsh sentencing

on white-collar crime. But much of his docket consisted of

methamphetamine cases, 87 percent of which required a mandatory

minimum as established in the late 1980s by lawmakers who had

hoped to send a message about being tough on crime.

By some measures, their strategy had worked: Homicides had

fallen by 54 percent since the late 1980s, and property crimes

had dropped by a third. Prosecutors and police officers had used

the threat of mandatory sentences to entice low-level criminals

into cooperating with the government, exchanging information

about accomplices in order to earn a plea deal. But most

mandatory sentences applied to drug charges, and according to

police data, drug use had remained steady since the 1980s even

as the number of drug offenders in federal prison increased by

2,200 percent.

“A draconian, ineffective policy” was how then-Attorney General

Eric H. Holder Jr. had described it.

“A system that’s overrun” was what Republican presidential

candidate Mike Huckabee had said.

“Isn’t there anything you can do?” asked Bennett’s wife, joining

him now in the living room. They rarely talked about his cases.

But he had told her a little about Weller’s, and now she wanted

to know what would happen.

“Childhood trauma is a mitigating factor, right?” she said.

“Shouldn’t that impact his sentence?”

“Yes,” he said. “Neglect and abuse are mitigating. Definitely.”

“And addiction?”

“Yes.”

“Remorse?”

“Yes.”

“No history of violence?”

“Yes. Of course,” he said, standing up. “It’s all mitigating.

His whole life is basically mitigating, but there still isn’t

much I can do.”

He could use a wake-up call. But, come on, I mean ... Ten years

is not a wake-up call. It’s more like a sledgehammer to the

face. He could use a wake-up call. But, come on, I mean ... Ten years

is not a wake-up call. It’s more like a sledgehammer to the

face.

Brad Hansen, Weller’s public defender

The first people into the courtroom were Weller’s mother, his

sister and then his father, who had driven 600 miles from Kansas

to sit in the front row, where he was having trouble catching

his breath. He gasped for air and rocked in his seat until two

court marshals turned to stare. “Look away,” he told them. “Have

a little respect on the worst day of our lives. Look the hell

away.”

In came Weller. In came the judge. “This is United States of

America versus Mark Paul Weller,” the court clerk said.

And then there was only so much left for the court to discuss.

Hansen, the defense attorney, could only ask for the mandatory

minimum sentence of 10 years, rather than the guideline sentence

of 13 years or the maximum of life. The state prosecutor could

only agree that 10 years was probably sufficient, because Weller

had a “number of mitigating factors,” he said. Bennett could

only delay the inevitable as the court played out a script

written by Congress 30 years earlier.

“This is one of those cases where I wish the court could do

more,” said Hansen, the defense attorney.

“He’s certainly not a drug kingpin,” the government prosecutor

consented.

“He could use a wake-up call,” Hansen said. “But, come on, I

mean . . .”

“He doesn’t need a 10-year wake-up call,” Bennett said.

“Ten years is not a wake-up call,” Hansen said. “It’s more like

a sledgehammer to the face.”

“We talk about incremental punishment,” Bennett said. “This is

not incremental.”

They stared at each other for a few more minutes until it was

time for Weller to address the court. He leaned into a

microphone and read a speech he had written in his holding cell

the night before, a speech he now realized would do him no good.

He apologized to his family. He apologized to the addicts who

had bought his drugs. “There is no excuse for what I did,” he

said. “I was a hardworking family man dedicated to my family. I

turned to drugs, and that was the beginning of the end for me. I

hope I get the chance to better my life in the future and put

this behind me.”

“Thank you, Mr. Weller. Very thoughtful,” Bennett said, making a

point to look him in the eye. “Very, very thoughtful,” he said

again, and then he issued the sentence. “You are hereby

committed to the custody of the bureau of prisons to be

imprisoned for 120 months.” He lowered his gavel and walked out,

and then the court marshal took Weller to his holding cell for a

five-minute visitation with his family. He looked at them

through a glass wall and tried to take measure of 10 years. His

grandmother would probably be dead. His daughter would be in

high school. He would be nearing 40, with half of his life

behind him. “It’s weird to know that even the judge basically

said it wasn’t fair,” he said.

Down the hall in his chambers, Bennett was also considering the

weight of 10 years: one more nonviolent offender packed into an

overcrowded prison; another $300,000 in government money spent.

“I would have given him a year in rehab if I could,” he told his

assistant. “How does 10 years make anything better? What good

are we doing?”

But already his assistant was handing him another case file, the

fifth of the day, and the courtroom was beginning to fill again.

“I need five minutes,” he said. He went into his office, removed

his robe and closed his eyes. He thought about the offer he had

received a few weeks earlier from an old partner, who wanted him

to return to private practice in Des Moines. No more sentencing

hearings. No more bathtub of guilt to drain. “I’m going to think

seriously about doing that,” Bennett had said, and he was still

trying to make up his mind. Now he cleared Weller’s sentencing

report from his desk and added it to a stack in the corner. He

washed his face and changed back into his robe.

“Ready to go?” his assistant asked.

“Ready,” he said. |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|